The change in the presidential administration has focused cannabis businesses on the potential for legalization nationwide.

Running parallel to full federal legalization will be a corresponding regulatory and taxation scheme replacing the current regime of IRC §280E which prohibits anything but the cost of goods sold being deducted from a state licensed cannabis operation’s income statement.

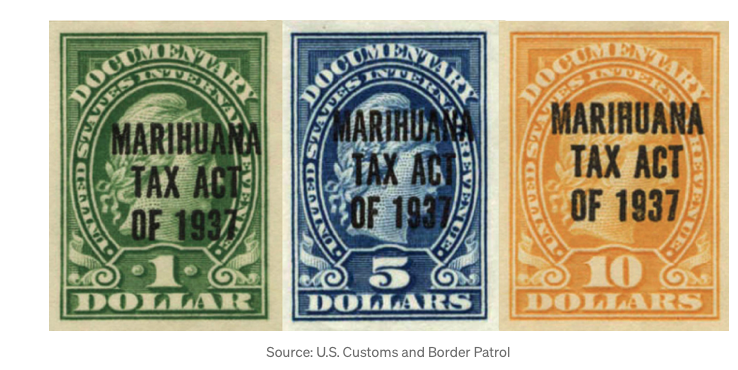

The evolution of the federal taxation of cannabis started with the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, which applied tax to marijuana used for medicine.

Historians and critics alike maligned this legislation as an attempt to stop the use of cannabis rather than tax it.

The fines were greatly out of line with any failure in tax compliance — violators were fined up to $2,000 and a potential prison sentence of up to five years, while the actual tax was merely $1 per ounce or $24 per year.

The Marijuana Tax Act was declared unconstitutional in Leary v. United States, and replaced with the Controlled Substances Act as Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970.1

Currently, the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act of 2019 (H.R. 3884) is primed to be debated in Congress, with many cannabis insiders expecting either passage, or a short deferral to allow the new administration time to attend to other immediate priorities demanding their attention nationwide.

The Terminally Flawed Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act of 2019

The Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act of 2019 (the “MORE Act”) has entered the end game of cannabis prohibition, and is externally palatable to lawmakers, cannabis producers, and most consumers.

The provision for federal taxation, according to an article published by The Tax Foundation, is a “modest” five percent excise tax on marijuana sales at the manufacturer’s level (emphasis added).2

This ad valorem tax (a form of taxation based on the assessed value of an item — think sales tax or real estate tax) would be imposed on manufactured cannabis as proposed in the amendment to IRC Section 5701 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 by “redesignating subsection (h) as subsection (i) and by inserting after subsection (g)….” which then defines “cannabis products.”

Essentially, the bill defines a “cannabis product” as “any cannabis or any article which contains cannabis or any derivative thereof.”

Where are the flaws in the bill?

The bill has issues in its perception by the consuming public, the anticipated revenue it will produce, and the actual use of the money generated by the excise tax.

Let’s examine each individually.

Perception by the Consuming Public

The entrenched black market for cannabis will enjoy a greater share of the market if the MORE Act passes due to the increased cost of legal marijuana.

In most states where cannabis is legal for recreational use (as well as some states offering medical marijuana) there is an additional sales tax imposed either at the point of sale or during the manufacturing process.

Per the IRS’s definition, “Excise taxes are often included in the price of the product.”3

If the MORE Act becomes law, unless the excise tax is imposed like alcohol and gasoline and remitted to the government by the manufacturer, consumers will balk at purchasing legal recreational cannabis, where the combined taxes may be 35% or higher.

Flaws in the Expenditure Model

The proposed revenue model for the MORE Act creates an “Opportunity Trust Fund,” with a distribution plan where the expenditures derived from net revenues are to be divided as follows:

“(c) Expenditures—Amounts in the Trust Fund shall be available, without further appropriation, only as follows:

“(1) 50% to the Attorney General to carry out section 3052(a) of part OO of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968.

“(2) 10% to the Attorney General to carry out section 3052(b) of part OO of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968.

“(3) 20% to the Administrator of the Small Business Administration to carry out section 5(b)(1) of the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act of 2019.

“(4) 20% to the Administrator of the Small Business Administration to carry out section 5(b)(2) of the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act of 2019.”

The 60% total provided to the Attorney General to carry out sections 3052(a) & (b) would be used exclusively to provide funding to 501(c)(3) nonprofits providing social services such as job training and substance abuse treatments.

The amendments to the legislation promulgated in H.R. 5385 under section 3052(a) and 3052(b) part OO would create the “Community Reinvestment Grant Program (CRGP),” “to provide eligible entities with funds to administer services for individuals most adversely impacted by the war on drugs,” and to provide funds for “Substance Use Treatment Services.”

CRGP would be overseen by a new Department of Justice regulation unit, The Cannabis Justice Office.

The remaining 40% to be expended per the legislation would be provided to the Small Business Administration, which would spend their share of the trust by funding loans to small businesses owned and controlled by “socially and economically disadvantaged individuals” working in the legal cannabis industry.

The bill adopts the definition of “socially and economically disadvantaged individual” contained in Section 8(d)(3)(C) of the Small Business Act which identifies these disadvantaged individuals as “Black Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, Asian Pacific Americans, and other minorities, or any other individual found to be disadvantaged [under the Small Business Act].”

Thus, there is no provision for general SBA loans to people seeking to enter the business, or any sort of government capital specifically earmarked by the SBA for loans to the general public looking to capitalize a new cannabis business.

The 60% of proposed collected excise tax is specifically earmarked for those most affected by the war on drugs, with the services available as defined above.

The Lack of Any New Medical Research Concerning the Effects of Cannabis

The Federal government has done very few studies on the long term consumption of cannabis due to its designation as a Schedule 1 drug with “no currently accepted medical use and high potential for abuse.”

The adoption of this bill would not earmark any funds for the research necessary to understand what sort of issues may arise in the future and how best to prepare for them.

Poor or Little Tax Guidance

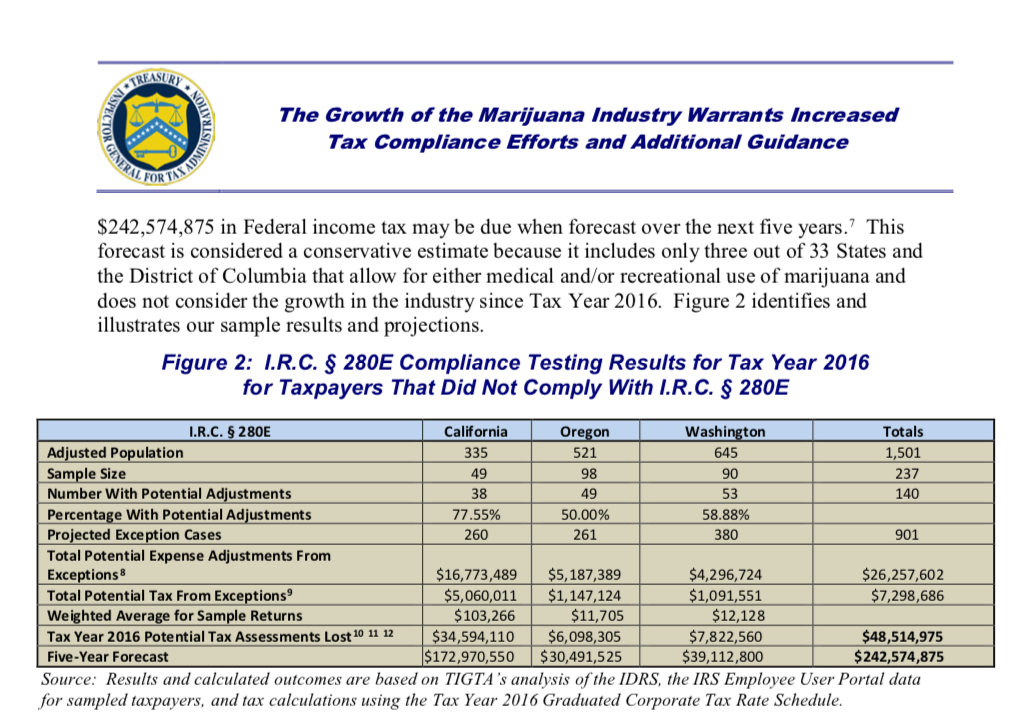

In a Final Audit Report (Audit #20180022, released March 30, 2020) prepared for the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service by Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration4, the contents revealed the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (“TIGTA”) had four specific findings, all of which demonstrated that both the tax structure and the mechanism for auditing and collecting further taxes was critically flawed, with little being done about it.

The audit used a very narrow sampling size, but the results still provided some important insights.

The Treasury Inspector:

i. “…determined that 59% (140 out of 237) of the tax return filings for Tax Year 2016 had likely IRC §280E adjustments, which when projected over the population totaled $48.5 million in unassessed tax year 2016, or $242.6 million the results are forecasted for five years.”

ii. The “tax impact to comply with IRC §280E… TIGTA estimated a $95 million Federal income tax impact to these taxpayers from the application of IRC §280E on their tax year 2016, or $475.1 million when forecasted over five years.”

iii. TIGTA additionally found through a random sampling of returns that IRC §61 issues were noted, with both under-reported income or non-filing of specific tax returns.

iv. The final issue according to TIGTA was that “the IRS lacks guidance to taxpayers and tax professionals in the marijuana industry.”

v. The implementation period of the act and the reporting requirements will generate a negative optics response by the consuming public.

The tax would go into effect one year after the MORE Act is implemented.

The MORE Act also directs the Bureau of Labor Statistics to regularly compile and publish a demographic survey of business owners and employees in the “cannabis industry,” including information about individuals’ age, race, sex, educational attainment, and veteran status.

Unless this information is directly extracted from original documentation submitted to state licensing board’s in original applications, this is another layer that will face pushback by the business community.

The Proper Model for The Federal Taxation of Cannabis

The MORE Act should be revised to reflect the true state of the cannabis industry, and the potential it holds.

There are a number of key issues that must be considered and implemented in order to fairly and efficiently tax the nascent cannabis industry.

The proper model for federal taxation must include:

i. Achieving a proper balance of taxation that will fund government mandated programs associated with the production and consumption of cannabis.

ii. A tax that is established at the manufacturing level such as alcohol and tobacco (so called “sin taxes”) rather than a tax added at the retail level in order not to discourage purchases, and to help disrupt the illegal marketplace.

iii. Rather than an ad valorem tax which will plateau quickly, and provide a falling revenue curve due to a drop in prices because of increased production, the taxation of cannabis should be done on a “specific taxation” basis like alcohol and gasoline, but on the actual THC level in the product.

For example, the current tax on alcohol is approximately $13.50 per gallon, or $2.67 per 750 milliliter bottle.

The tax is added at the manufacturing level, not at the retail level in order not to give the purchases sticker shock when viewing the receipt, and to provide a wholesale formula that is easier to track for the producer.

This method provides for a consistent, defined purchase price allowing the consumer to easily compare prices.

iv. In order to increase the legal market and hamper illegal operations, the taxation should be done at different levels for different products utilizing the specific taxation model, so consumers can also be guided toward lower levels of consumption thereby avoiding larger scale payments

of funds for “externalities,” which are the issues that arise from the consumption of a product and require use of the collected funds.

A parallel externality would be the use of cigarette taxes to help combat underage smoking by creating advertising campaigns.

v. The government should ensure that cannabis taxation is indexed (unlike alcohol taxes) to prevent the effects of inflation reducing the spending power of the money collected.

Preparing the IRS for the Collection of Cannabis Taxes

The TIGTA report should be used as a preliminary blueprint for the taxation, education, and compliance necessary for the cannabis industry.

The report highlights the majority of tax returns submitted to the IRS have mistakes totaling millions of dollars in underpayment of taxes.

Is the issue strictly a lack of knowledge in the preparation of tax returns for Schedule I substances?

The answer is a resounding no.

Despite the data from 2016, it is important to note that almost all cannabis companies use CPA’s or other tax professionals to help document and prepare their state and federal tax returns.

On the federal level per 26 U.S. Code § 6662 , there is an accuracy-related penalty of 20% of the underpayment assessed against the tax return preparer.

In 2016, there were any number of tax professionals involved in the preparation of cannabis licensed businesses, but according to the Treasury the returns were almost 60% of the time prepared incorrectly, subjecting these preparers to fines, and other sanctions.

Given these statistics, the taxation and collection of cannabis-based taxes upon the presumed overturning of the illegality of the plant should be modified to prevent the current issues.

The IRS should be creating substantial documentation for both the taxpayer and the tax preparer in the form of guidance bulletins, tax forums, video instructions, and taped seminars.

All of these are currently in use by the IRS under their website for “IRS Training and Communication Tools for Tax Professionals.”

The proper method of taxation, accompanied by the proper tax remittance by the manufacturer as opposed to the retailer, will help reduce the illicit marketplace by avoiding consumer perception of onerous taxes placed on cannabis to prevent consumption.

It will also spur the creation of different forms of ingestible recreational cannabis, to help reduce the price for consumer acceptance based on lower levels of THC in the saleable product.

Estimated Tax Revenue of Federally Legal Cannabis

According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “state and local excise collections on retail cannabis sales surpassed $1 billion for the first time in 2018.”5

This rapid growth is aligned with the acceptance of medical and recreational cannabis, and the efforts states are putting in to help discourage purchasing cannabis from unlicensed and untaxed sources.

The report also points out that in both Colorado and Nevada, “the cannabis excise taxes already rival total excise tax revenues collected from all forms of alcohol including beer, wine, and liquor.”

The estimated tax revenue is going to be a bell-shaped curve due to its original acceptance, rapid growth and collection of taxes, along with a steep decline in prices that will create the descending part of the graphed collections (unless demand offsets cost).

The estimated tax revenue derived from legalized cannabis is going to be large, but will not impact the overall economy.

The Washington Post has utilized a report from New Frontier Data, that states “legalizing marijuana would create at least $132 billion in tax revenue… in the next decade.”

This number, although substantial, pales in comparison to other sources of taxes collected by the federal government.

Conclusion

When recreational cannabis is legalized and taxed, additional issues must be sorted out to create a robust, well-regulated industry.

Once legalized, as a consumable, it will also be regulated by the FDA along with existing government agencies that already have responsibility for monitoring workplace safety, employee safety, etc.

The large number of licensed facilities will help shape the business law, but the application of the taxation scheme will come from trained professionals in the IRS.

It is incumbent that they are provided proper documentation, training, guidance manuals, and peer review to ensure across the board application of the rules.

The actual form of taxation recommended, “the specific taxation” model, may be too difficult to integrate into different state revenue models that already use a flat excise tax based on weight.

However, rather than look for the immediate solution, it is imperative the federal government and the legislators who craft tax policy understand the business model for licensed cannabis production, and understand the expected decline in prices upon the anticipated federal legalization of cannabis.